Hulk (ship type)

A hulk is a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea. Hulk may be used to describe a ship that has been launched but not completed, an abandoned wreck or shell, or to refer to a ship whose propulsion system is no longer maintained or has been removed altogether. The word hulk also may be used as a verb: a ship is "hulked" to convert it to a hulk. The verb was also applied to crews of Royal Navy ships in dock, who were sent to the receiving ship for accommodation, or "hulked".[1] Hulks have a variety of uses such as housing, prisons, salvage pontoons, gambling sites, naval training, or cargo storage.

In the age of sail, many hulls served longer as hulks than they did as functional ships. Wooden ships were often hulked when the hull structure became too old and weak to withstand the stresses of sailing.

More recently, ships have been hulked when they become obsolete or when they become uneconomical to operate.

Sheer hulk

[edit]A sheer hulk (or shear hulk) was used in shipbuilding and repair as a floating crane in the days of sailing ships, primarily to place the lower masts of a ship under construction or repair. Booms known as sheers were attached to the base of a hulk's lower masts or beam, supported from the top of those masts. Blocks and tackle were then used in such tasks as placing or removing the lower masts of a vessel under construction or repair. These lower masts were the largest and most massive single timbers aboard a ship, and erecting them without the assistance of either a sheer hulk or land-based masting sheer was extremely difficult.

The concept of sheer hulks originated with the Royal Navy in the 1690s, and persisted in Britain until the early nineteenth century. Most sheer hulks were decommissioned warships; Chatham, built in 1694, was the first of only three purpose-built vessels.[2] There were at least six sheer hulks in service in Britain at any time throughout the 1700s. The concept spread to France in the 1740s with the commissioning of a sheer hulk at the port of Rochefort.[3]

By 1807 the Royal Navy had standardised sheer hulk crew numbers to comprise a boatswain, mate and six seamen, with larger numbers coming aboard only when the sheers were in use.[3]

-

Portsmouth Harbour with prison hulks

-

A fleet of ships and hulks in Portsmouth harbour

-

Sheer hulk at Sheerness Dockyard positioned to make a lift

-

Model of the decommissioned 50-gun ship Entreprenant, formerly in the collection of Duhamel du Monceau and now on display at the Musée national de la Marine in Paris

-

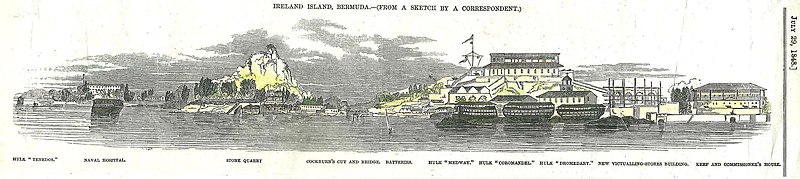

The Grassy Bay anchorage seen from the Royal Naval Dockyard in Bermuda in 1865, with the hulk of HMS Medway tied to the wharf and another hulk anchored at Grassy Bay.

Accommodation hulk

[edit]

An accommodation hulk is a hulk used as housing, generally when there is a lack of quarters available ashore. An operational ship may be used for accommodation, but a hulk can accommodate more personnel than the same hull would accommodate as a functional ship. For this role, the hulk is often extensively modified to improve living conditions. Receiving hulks and prison hulks are specialized types of accommodation hulks. During World War II, purpose-built barracks ships were used in this role.

Receiving hulk

[edit]

A receiving ship is a ship used in harbour to house newly recruited sailors before they are assigned to a ship's crew.[4]

During the wars of the 18th and 19th century, almost every nation's navy suffered from a lack of volunteers[5][6] and had to rely on some form of forced recruitment.[7][8][9] The receiving ship partly solved the problem of unwilling recruits escaping; it was difficult to get off the ship without being detected, and most seamen of the era did not know how to swim.[10]

Receiving ships were typically older vessels that could still be kept afloat, but were obsolete or no longer seaworthy. The practice was especially common in the age of wooden ships, since the old hulls would remain afloat for many years in relatively still waters after they had become too weak to withstand the rigors of the open ocean.[citation needed]

Receiving ships often served as floating hospitals as many were assigned in locations without shore-based station hospitals. Often the afloat surgeon would take up station on the receiving ship.[citation needed]

Prison hulk

[edit]

A prison hulk was a hulk used as a floating prison. They were used extensively in Great Britain, the Royal Navy producing a steady supply of ships too worn-out to use in combat, but still afloat. Their widespread use was a result of the large number of French sailors captured during the Seven Years' War, and continued throughout the Napoleonic and French Revolutionary Wars a half-century later. By 1814, there were eighteen prison hulks operating at Portsmouth, sixteen at Plymouth and ten at Chatham.[3]

Prison hulks were also convenient for holding civilian prisoners, commencing in Britain in 1776 when the American Revolution prevented the sending of convicts to North America. Instead, increasingly large numbers of British convicts were held aboard hulks in the major seaports and landed ashore in daylight hours for manual labour such as harbor dredging.[3] From 1786, prison hulks were also used as temporary gaols (jails) for convicts being transported to Australia.

Hulks used for storage

[edit]A powder hulk was a hulk used to store gunpowder. The hulk was a floating warehouse which could be moved as needed to simplify the transfer of gunpowder to warships. Its location, away from land, also reduced the possible damage from an explosion.

Service as a coal hulk was usually, but not always, a ship's last.

Of the fate of the fast and elegant clipper ships, William L. Carothers wrote, Clippers functioned well as barges; their fine ends made for little resistance when under tow ... The ultimate degradation awaited a barge. There was no way up, only down-- down to the category of coal hulks ... Having strong solid bottoms ... they could handle the great weight of bulk coal which filled their holds. It was a grimy, untidy, unglamorous end for any vessel which had seen the glory days.

[11]

The famed clipper Red Jacket ended her days as a coaling hulk in the Cape Verde Islands.

One by one these old Champions of the Seas disappeared. The Young America was last seen lying off Gibraltar as a coal hulk; and that superb old greyhound of the ocean, the Flying Cloud suffered a similar ignominious ending. She was not even spared the humiliation of concealing her tragic end from the eyes of her former envious rivals, but was condemned to end her days as a New Haven scow towed up the Sound with a load of brick and concrete behind a stuck up parvenu tug. Ever and anon as if to emphasize her newly acquired importance, the tug would bury the old-time square-rigged beauty in a cloud of filthy smoke. Imagine the feelings of an ex-Cape Horner under such conditions! There should have been a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Old Clippers. Everybody who knows anything about ships, knows that they have feelings just the same as anybody else.[12]

— Henry Collins Brown, (1919), The Clipper Ships of Old New York, Valentine's Manual of Old New York, Issue 3, p. 94-95

Salvage pontoon

[edit]

Hulks were used in pairs during salvage operations. By passing heavy cables under a wreck and connecting them to two hulks, a wreck could be raised using the lifting force of the tide or by changing the buoyancy of the hulks.

Hulk assemblages

[edit]A hulk assemblage (sometimes known as a ship graveyard) is where more than one vessel has been hulked in the same location.[13] A project by Museum of London Archaeology (with the Thames Discovery Programme and the Nautical Archaeology Society) and in 2012 created a database of known hulk assemblages in England. They identified 199 separate hulk assemblages ranging in size from two vessels to over 80.[14]

Hulks in modern times

[edit]Several of the largest former oil tankers have been converted to floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) units, effectively very large floating oil storage tanks. Knock Nevis, by some measures the largest ship ever built, served in this capacity from 2004 until 2010. In 2009 and 2010, two of the four TI-class supertankers, then the largest ships afloat, TI Asia and TI Africa, were converted to FPSOs.

Other services

[edit]A vessel's hulking may not be its final use. Scuttling as a blockship, breakwater, artificial reef, or recreational dive site may await. Some are repurposed, for example as a gambling ship; others are restored and put to new uses, such as a museum ship. Some even return revitalised to sea.

When lumber schooner Johanna Smith, "one of only two Pacific Coast steam schooners to be powered by steam turbines,"[15] was hulked in 1928, she was moored off Long Beach, California and used as a gambling ship until destroyed by a fire of unknown cause.

One vessel rescued from this ignominious end was the barque Polly Woodside, now a museum ship in Melbourne, Australia. Another is the barque James Craig, rescued from Recherche Bay in Tasmania, now restored and regularly sailing from Sydney, Australia.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Log of HMS Tamar, 10 April 1914 "1·30 Welland Ship Company hulked on board"

- ^ Harrison, Cy (2016). "British Other Vessels sheer hulk Chatham Hulk (1694)". Three Decks.

- ^ a b c d Gardiner, Robert; Lavery, Brian, eds. (1992). The Line of Battle: The Sailing Warship 1650–1840. Conway Maritime Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-85177-954-9.

- ^ "Receiving Ship". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ Lavery, Brian (2012). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1793–1815. Conway Maritime Press. p. 289. ISBN 9781591146124.

- ^ Roger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World - An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. London: Fontana Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-00-686152-2.

- ^ Lavery, Brian (2012). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1793-1815. Conway Maritime Press. pp. 281, 284. ISBN 9781591146124.

- ^ Lambert, Andrew (2000). War at Sea in the Age of Sail. Strand, London.: Cassell. p. 46. ISBN 0-304-35246-2.

- ^ Roger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World - An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. London: Fontana Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-00-686152-2.

- ^ Lavery, Brian (2012). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1793–1815. Conway Maritime Press. pp. 144, 189. ISBN 9781591146124.

- ^ Crothers, William L (1997). The American-built clipper ship, 1850–1856: characteristics, construction, and details. Camden, ME: International Marine. ISBN 0-07-014501-6.

- ^ Brown, Henry Collins (1919). "The Clipper Ships of Old New York". Valentine's Manual of Old New York. 3. New York: Valentine's Manual: 94–95. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Thames Discovery Programme – Hulk Assemblages Survey". www.thamesdiscovery.org. Retrieved 2022-03-02.

- ^ Museum Of London Archaeology (2012–2013), Hulk Assemblages: Assessing the national context, Archaeology Data Service, doi:10.5284/1011895

- ^ "Johanna Smith". California Wreck Divers. 2001.